Anaemia has been acknowledged as a frequent systemic complication and/or extraintestinal manifestation in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)1 with iron deficiency (ID) being the primary cause of disease2 with an estimated prevalence of iron deficiency anaemia (IDA) among patients with IBD at approximately 45 %.3

Considering the potential effect on hospitalization rates and consequences for patients quality of life, anaemia has been described as a significant and costly complication of IBD.4 However, ID and IDA are under-treated.5

The pathogenesis of ID in IBD is complex, comprising intestinal bleeding, malabsorption, and inadequate oral intake.3 As symptoms of IDA mimic the symptoms of the disease such as fatigue,6 regular screening and diagnosis in these patients are crucial to uncover ID and IDA and therapy of anemia may even improve the quality of life better than the therapy of disease activity.5

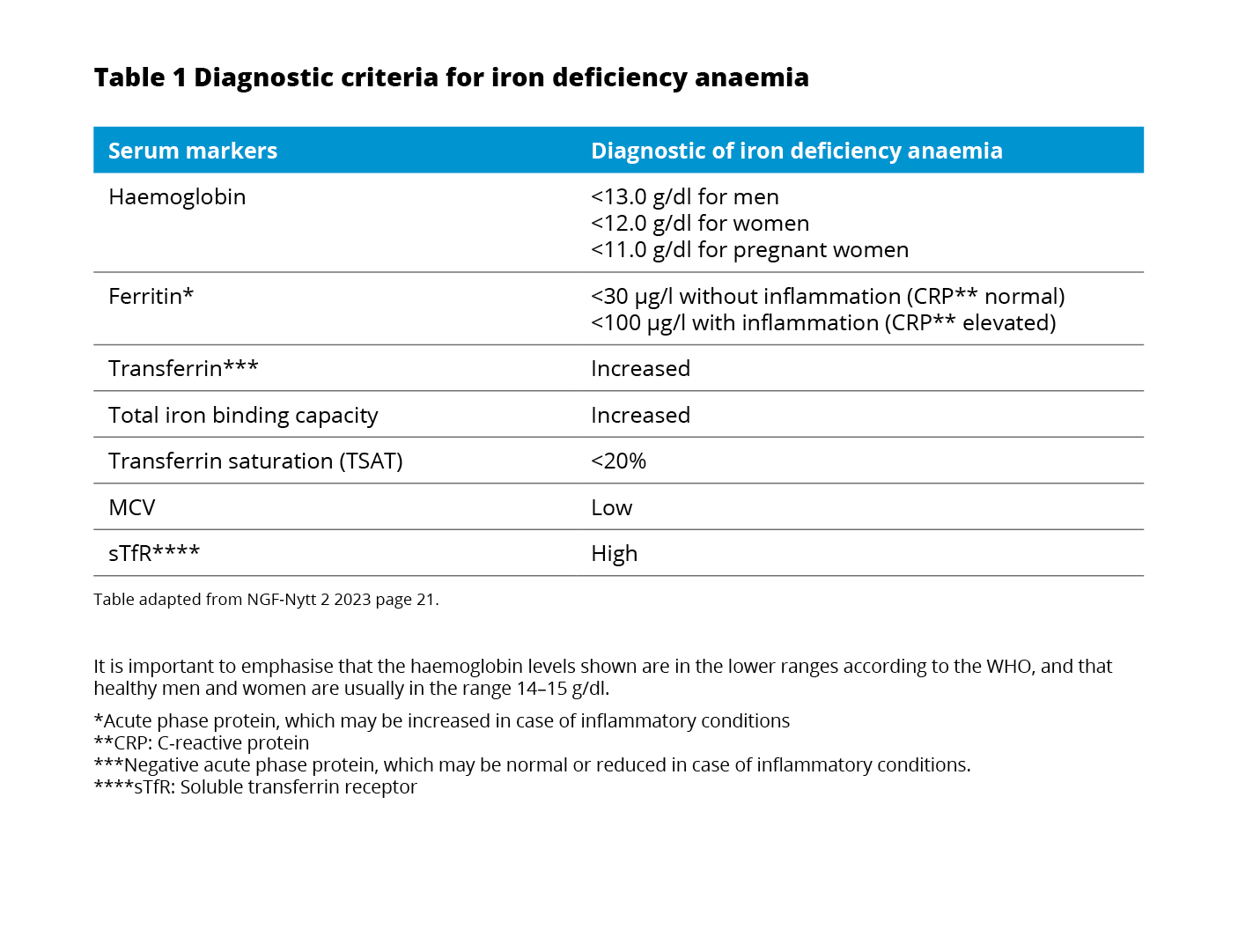

The currently used WHO definition of anaemia7 also applies to patients with IBD.8 All patients with IBD should be assessed for the presence of anaemia through laboratory testing of blood count, serum ferritin, and C-reactive protein every 6-12 months.8

If the hemoglobin (Hb) is below normal, anaemia workup should be initiated including red blood cell distribution width (RDW) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV), reticulocyte count, differential blood cell count, serum ferritin, transferrin saturation (TSAT), and CRP concentration.8

Even when IBD patients are screened, ID and IDA might be overlooked as commonly used laboratory tests may be compromised due to several pathophysiological mechanisms related to the inflammatory nature of IBD9

Consequently, when evaluating ID and IDA in IBD the following mechanisms should be taken into consideration:

Hemoglobin: Iron deficiency should not be excluded despite normal Hb as Hb levels do not decline until a significant amount of iron is lost.10

Ferritin: Besides binding and storing iron in the liver, spleen, and reticuloendothelial system ferritin is also an acute-phase protein and can be increased in the presence of inflammation.11 Following, the interpretation of serum ferritin in patients with inflammation is tricky.5

Hepcidin and ferroportin: The hepatic peptide hormone hepcidin functions as an important regulator of iron homeostasis by controlling ferroportin – the sole iron exporter. However, hepcidin also increases as a response to inflammation.13 The increased levels of hepcidin caused by inflammation will promote the degradation of ferroportin and subsequently impair the exportation of cellular iron into plasma.13

Transferrin saturation: The main iron carrier protein is transferrin.6 In the presence of inflammation, a normal ferritin level does not exclude ID.14 In this case, testing TSAT provides an indication of the extent of iron utilization.10

Soluble transferrin saturation receptor: The TSAT level only indicates the extent of iron utilization.4 A more extensive workup should include soluble transferrin receptor (sTfR) testing.8 sTfR is a truncated form of the cellular transferrin receptor and circulates bound to transferrin.10 It is released in proportion to the expansion of erythropoiesis in the bone marrow and is not regulated by inflammation.5 As a reflector of erythropoiesis, sTfR correlates with the amount of iron available.

Iron supplementation is recommended by The European Chron’s and Colitis Organisation (ECCO) in all IBD patients with IDA with the goal of normalizing hemoglobin levels and iron stores.8

While oral iron substitution is safe, affordable, and easy to administer it might not be the perfect solution for patients with IBD:3

Hence, IV iron therapy is considered first-line treatment for patients with active disease, severe anemia, oral iron intolerance, and erythropoietin requirements.3,8

Note: Vennligst se den fullstendige preperatomtalen før produktet forskrives.

Legemiddelform: Infusjons-/injeksjonsvæske, jern(III)derisomaltose, oppløsning 100 mg/ml. Tilgjengelig som hetteglass: 5 x 1 ml, 5 x 5 ml og 2 x 10 ml. Indikasjoner: Behandling av jernmangel ved følgende indikasjoner: Ved klinisk behov for hurtig tilførsel av jern. Når orale jernpreparater ikke kan benyttes pga. manglende effekt eller ikke kan brukes av andre årsaker. Diagnosen må baseres på laboratorieprøver. Dosering: Doseringen gjøres trinnvis: [1] bestemmelse av det individuelle jernbehovet, og [2] utregning og administrasjon av jerndosen(e). Trinnene kan gjentas etter [3] vurdering av jernoppfylling etter jerntilskudd. Jernbehovet er uttrykt i mg elementært jern. Jernbehovet kan bestemmes enten ved en forenklet tabell basert på Hb-verdi og kroppsvekt eller ved Ganzoni-formelen (se preparatomtalen). For å vurdere effekten av Monofer skal Hb-nivået revurderes tidligst 4 uker etter siste administrering. Ved ytterligere behov for jern, må dette utregnes på nytt. Administrasjon: Preparatet gis som i.v. bolusinjeksjon, som i.v. infusjon eller som en injeksjon direkte i veneslangen ved hemodialyse. I.v. bolusinjeksjon: Doser opptil 500 mg pr. injeksjon opptil 3 ganger ukentlig og med injeksjonshastighet på opptil 250 mg jern/minutt kan tilføres. Dosen kan gis ufortynnet eller fortynnes. I.v. infusjon: Hele jerndosen, opptil 20 mg jern/kg kroppsvekt, kan gis som én engangsinfusjon eller som ukentlige infusjoner til det kumulative jernbehovet er gitt. Dersom jernbehovet overstiger 20 mg jern/kg kroppsvekt, må dosen deles opp i 2 administreringer med minst 1 ukes mellomrom. Det anbefales, når det er mulig, å gi 20 mg jern/kg i 1. administrering. Avhengig av klinisk skjønn kan 2. administrering avvente oppfølgende laboratorieprøver. Skal infunderes ufortynnet eller fortynnet, med steril 9mg/ml natriumkloridoppløsning, i maksimalt 500 ml. Kontraindikasjoner: Overfølsomhet for innholdsstoffene eller kjent overfølsomhet for andre parenterale jernpreparater. Anemi uten at det foreligger jernmangel (f.eks. hemolytisk anemi). For høyt jernnivå eller forstyrrelser i kroppens utnyttelse av jern (f.eks. hemokromatose, hemosiderose). Dekompensert leversykdom. Forsiktighetsregler: Parenteralt administrerte jernpreparater kan gi overfølsomhetsreaksjoner, inkl. alvorlige og potensielt dødelige anafylaktiske/anafylaktoide reaksjoner. Overfølsomhetsreaksjoner er også sett etter tidligere bivirkningsfrie doser av parenterale jernkomplekser. Overfølsomhetsreaksjoner som har utviklet seg til Kounis syndrom er sett. Risikoen er økt ved kjente allergier. Pasienten bør observeres for bivirkninger i minst 30 minutter etter hver administrasjon. Behandlingen må stoppes umiddelbart ved overfølsomhetsreaksjoner eller tegn på intoleranse under administrering. Parenteralt jern bør brukes med forsiktighet til pasienter med akutt eller kronisk infeksjon. Bør ikke gis til pasienter med aktiv bakteriemi. Overfølsomhets-reaksjoner kan oppstå, hvis IV injeksjonen gis for hurtig. Bivirkninger: Akutte, alvorlige overfølsomhetsreaksjoner kan forekomme ved administrering av parenterale jernpreparater. De opptrer vanligvis i løpet av de første minuttene etter infusjonsoppstart og er karakterisert ved plutselig innsettende pustebesvær og/eller sirkulatorisk kollaps. Vanlige: Kvalme, utslett, reaksjoner på injeksjonsstedet. Vennligst se den komplette preperatomtale for opplysninger om alle bivirkninger. Graviditet: Det er begrenset data på bruk av Monofer hos gravide kvinner, dette fra en studie med 100 behandlede gravide kvinner. En grundig nytte/risiko-vurdering er påkrevd før bruk under graviditet. Behandling med Monofer bør begrenses til andre og tredje trimester.

Ytterligere sikkerhetsinformasjon: Bør ikke brukes til barn og ungdom <18 år. Kan gi overfølsomhetsreaksjoner, inkl. alvorlige og potensielt dødelige anafylaktiske/anafylaktoide reaksjoner. De opptrer vanligvis i løpet av de første minuttene etter infusjonsoppstart og er karakterisert ved plutselig innsettende pustebesvær og/eller sirkulasjonssvikt. Overfølsomhetsreaksjoner som har utviklet seg til Kounis syndrom er sett. Risikoen er økt ved kjente allergier og ved autoimmune eller inflammatoriske tilstander. Behandlingen må stoppes umiddelbart ved overfølsomhetsreaksjoner eller tegn på intoleranse under administrering.

Pakninger og priser (per 09/22): ATC: B03AC. Hetteglass: 5 x 1 ml kr 1532,40. 5 x 5 ml kr 7203,10. 2 x 10 ml kr 5770,60.

Reseptgruppe C

Basert på SPC godkjent 11.08.2022.

For ytterligere informasjon om Monofer®, se SPC. www.felleskatalogen.no

Innehaver av markedsføringstilatelsen: Pharmacosmos A/S, Rørvangvej 30, DK- 4300 Holbæk, Danmark www.pharmacosmos.com.

07-SCAN-11-09-2023.v1

PHOSPHARE-IBD study presentation

Gastro advertorial Norway

Cardio advertorial Norway

Gastroenterology article 2